Malleable Identity, Molded Identity

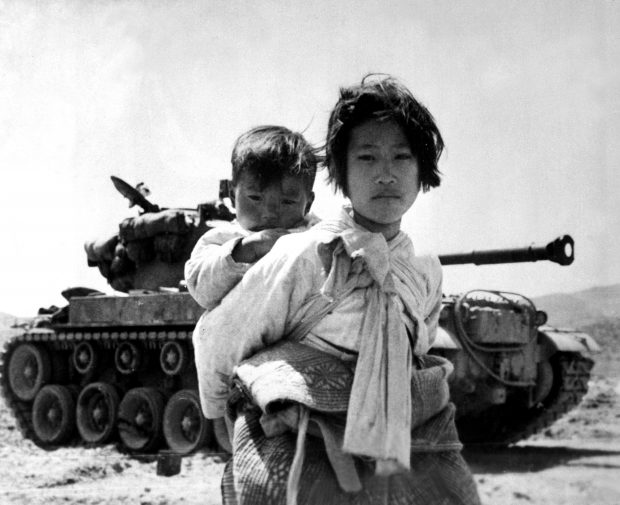

With her brother on her back, a war weary Korean girl tiredly trudges by a stalled M-26 tank, at Haengju, Korea. June 9, 1951. Maj. R.V. Spencer, UAF. (Navy)

NARA FILE #: 080-G-429691

WAR & CONFLICT BOOK #: 1485

What makes you you? Is it your fingerprint? Maybe the passport you show to the officer before your flight. At any first meeting, people will ask one another, “What’s your name?”, “Your job?”, or “Where are you from?”. And then you will go down the list, describing yourself according to facts that were decided for you before your birth.

By all means, our ID photos and personal information tell others about ourselves in a most objective and clear manner, but is that all there is to us?

Identity—a term that has become so familiar and widely used that we do not stop to think what it specifically refers to. Dictionary.com has it that identity is the condition of being oneself, or itself, and not another. A second definition says that the word is the condition or character as to who a person or what a thing is; the qualities, beliefs, etc., that distinguish or identify a person or thing.

That in mind, a mere passport could not describe the scope of our existence, let alone the values behind our every thought and action. Psychologists and researchers thus have tried to classify the many types of identity that makes each individual unique to themselves. Some of the largest categories include: racial, socio-cultural, gender, religious, online, and occupational identity.

But even with this breakdown, as is expected of our complicated world, there are even more underlying layers to each of the different identities. For instance, gender itself cannot be seen as the conventional female and male dichotomy. LGBT groups and a new “third gender—the Hijra (intersex) gender of South Asia—break existing boundaries, seeking a more comprehensive overview of sexuality.

For the sake of space and time, our April Magazine N looks into racial and socio-cultural identity, which is often considered the most basic identity that humans are associated with, and also the easiest to describe, or so it seems at first. In our future issues, we will offer more detailed descriptions of the various identities mentioned above to give as honest a depiction of humanity as we can. -Reporters’ Note

The race that we are, the culture we live

“They don’t know who I am; what they do know, is that I’m not nothing, and that I’m not no one.” -Justin K. McFarlane Beau.

Race and ethnicity usually tell us a lot about a person’s culture, explaining why and how a person would behave in any particular situation. The country of our nationality and the people we owe our ethnic origins to mark a significant portion of our language, mannerisms, and the particular way we regard the world around us.

Still, a distinction must be made of racial and socio-cultural identity in that while the former is generally an overt (visible) expression, cultural identity is a covert indication of a person’s inner self. A woman may have a dark brown skin-tone may not altogether think like an African; neither does a man whose passport reads that he is from the United States of America mean he will be white-skinned and tall.

There are so many exceptions to any single race that to classify individuals according to a racial context is next to meaningless, especially in such a globalized era. Though it is not always the case, we may be culturally entirely different from who we are racially.

Why does this even matter?

Well, only because identity formation is in our blood. According to psychologist Abraham Maslow’s famous “Hierarchy of Needs” in his 1943 paper, A Theory of Human Motivation, human beings must be satisfied of various needs depending on the level of urgency. When we are provided with our physiological (health, shelter, food) needs, we naturally desire an upward movement towards esteem and self-actualization which have to do with finding the meaning of our existence; who we are, and why we are.

And a large part of those questions is answered through the internal process of belonging to a group—one’s awareness of nationality, religion, social class, generation, family, and friends; these are a deciding factor of the way we perceive ourselves. Community makes all the difference in bridging cultural and socio-cultural identity to balance.

But what happens when one’s race, nationality, and culture go out of balance? The official term for that is culture shock. People who experience living in multiple countries may be fortunate in being able to visit many places, but when this goes on for extended periods, suddenly one struggles with identifying where they feel most included and at home.

Studies show that there are four stages to adjusting to a new environment: first it’s the Honeymoon stage, when travelers are infatuated with their surroundings and are positive about the future, then comes the Culture Shock, when the disturbing reality of social differences become more irritating until they reach Gradual Adjustment to finally feeling at home in Acceptance of the place they live in (Medium.com).

The amount of resetting that goes on in the mind is significant enough to say that a person’s identity is likewise, altered, despite their outward image being the same. It just goes to show that neither cultural nor racial identity is fixed, prodding us once more to the fact that we must never assume anything about our neighbors.

Read more about a number of cultural and racial groups found in Korea and the nuances to their personal stories.

Where is Home?

Korean Diaspora and the Gyopo

There are multiple reasons why people choose or have to leave their homeland. When the scale of people spreading from one original country to another is big, that’s referred to as diaspora. And according to Cohen’s theory, there are different types of diasporas such as imperial or colonial, victim or refugee, labor or service, and trade or commerce. Diaspora in terms of Korea comes with important historical significance. The fact is that although Korea is still largely monocultural and the people are strongly rooted in their homeland, around 7 million ethnic Koreans live abroad. Such overseas Koreans are concentrated mainly in 5 countries: the United States, China, Japan, CIS, and Canada.

This phenomenon has become so relevant that a term was created to refer to a specific portion of the Korean diaspora. Gyopo, also spelled kyopo, defines a native Korean who permanently resides in another country—even if said person will return to Korea in the future. There are several variations to this word such as dongpo, meaning “brethren” or “people of the same ancestry,” or gyomin (meaning “immigrants”). Moreover, different terms are applied based on the countries of residency of the diaspora: the prefix je-mi gyopo indicates a gyopo based in the United States, while je-il indicates a gyopo residing in Japan.

Nevertheless, in this complex situation of terminology and definitions, people’s lived experience is what really matters. For sure, there is something special in having grown up abroad with Korean parents. What accounts for this identity shift? Which language would be considered one’s native, or mother tongue? And what challenges would such people face living in a starkly different cultural environment?

Sarah (alias), 33, considers herself a blasian, black Asian, woman. Raised by a Korean mother and an African American father, she was born in Germany and grew up in the US. Now, Sarah is based in Korea where she works as a teacher. In the past, she had difficulty coming to terms with her identity. “My biggest time of identity crisis was during elementary school. I had all types of friends, mostly white, and I wanted to be like them. In most of the movies that come out during my childhood, the female leads were always white. I wanted to look like them. When I started middle school, my friend demographic became mostly African American friends plus white people. I learned to be myself then,” she said, recalling her past.

Meanwhile, Lily (Hye-Young) is a 42-year-old translator and interpreter. Born and raised in Germany by Korean parents, she now lives in Daejeon. She introduced herself as a German-born Korean who considers Germany her true home. But, she has had her own difficulties with identity.

Asked about her personal experience, Lily said, “During the 80s and 90s, there was no representation of Asians on German TV or Western media in general. Korea was hardly known at the time. The perception changed a little with the 1988 summer Olympics, and later with the 2002 FIFA World Cup. As a child and teenager, I spent years pondering whether I was German, Korean, Korean German, or German Korean…or simply both. But in retrospect, I can say that I have always been more German than Korean and I still feel this way now. Even if I love Korean food and speak Korean like a native speaker; even if I follow all the rules to Korean social hierarchy, I was born and raised in Germany, so of course I have been shaped and influenced by Western culture.” Like many other gyopo, Lily learnt Korean first, but she considers German her mother tongue.

Koreans Adopted by Foreign Parents

Since the end of World War II and the Korean War, over 200,000 Korean children were adopted abroad according to the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. These children were mainly adopted either because they were born to poor families, they were mixed, or they had single mothers. Agencies such as Holt International Children’s Services and Social Welfare Society handled, and still handles, the adoption process.

As many adoptees have come back to live in their native (birth) country, and have shared their stories, it is becoming clear that international adoption should not be the first choice in ensuring a future for children born into disadvantaged situations. In fact, many adoptees have been advocating for an end to international adoptions, supporting the idea that better national welfare and domestic adoptions should be the prior choices for such children. Adoptees, together, also created organizations that offer different kinds of support systems such as DNA testing and reunification programs with the biological family, post-adoption services such as tours around Korea, Korean language programs scholarship, help with attaining the F4 visa (which allows Korean adoptees to reside and legally work in Korea), and many more services.

Raising awareness of the issues related to international adoption is a significant goal of such organizations run by Korean adoptees. Many of them admit to having experienced some form of identity crisis, discrimination, racial alienation, and depression and records are showing that separation from one’s mother, fear of disappointing adoptive parents, and shock from having to live among people who look different result in the high level of depression, suicide, drug and alcohol consumption cases found amongst adopted individuals (4.5 percent of adopted individuals struggle with drug abuse-related issues compared to 2.9% amongst the general population, according to the Huffington Post).

Back in Korea, when they return, these adoptees are faced with altogether new problems. For instance, some adoptees felt discriminated in Korea as well, mostly because they were not able to speak the language. At the same time, this was not the case for other adoptees who came to Korea. “Many adoptees think they are discriminated in Korea, but I think they are projecting. I’ve never had problems even if I speak only a little Korean,” said Kristin, 41. “I was born here, I live here. I consider Korea my home”. Raised in the US, in 2013, Kristin came back to Korea to work as a professor. “I cannot say I really had identity issues because I lived in New York City, so there was no cultural shock. I speak English more in Korea than in the US, where I spoke mostly in Spanish (laughing). However, coming back here I am basically illiterate since I do not speak Korean. Thus, I can’t vote. Having no civil knowledge and being unable to participate is a problem for someone like me,” she added.

Tammy, another professor based in Seoul, also recognizes Korea as her home. “In the US, I was considered a person of color and a migrant. While here (in Korea), I consider myself a remigrant.” With a smile on her face, Tammy explained the daily issues she experienced in public offices and banks; places where workers did not know how to legally handle her situation as an adoptee now living in Korea.

North Koreans in South Korea

Since the division of the Korean peninsula at the end of the Korean War (1950–1953), some North Koreans have managed to defect from their home country. Officially called defectors, in South Korea they are also called northern refugees (tal-buk-ja) and new settlers (sae-teo-min). According to the Korean Ministry of Reunification, since 1998, 31,339 defectors entered South Korea. Among these, 8,993 are male defectors while 22,346 are female. They escape to South Korea looking for a better life and better opportunities.

But this process is not always linear and easy. For instance, Mr. Kwon, after defecting and experiencing life in the South, asked to be returned to his homeland. “In South Korea, people called me names, treating me like an idiot, and did not pay me as much as others for the same work, just because I was from the North,” he said in an interview with The New York Times.

Kim Dan-bi, a 26-year-old defector who lived in South Korea for 6 years, further said that it is hard to put up with discrimination from South Koreans. For these reasons, many North Korean defectors no longer put up with living amongst their southern neighbors, quitting South Korea for more hospitable countries.

The Korean Chinese in Korea

They are an ethnic minority from mainland China but with Korean roots—many the descendants of Korean emigrants of the Qing dynasty. Chosunjok (literally meaning ethnic group of Koreans) are a Korean Chinese population largely found in Northeast China, especially Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture. Since the late 1980s, numerous Chosunjok moved to South Korea, the “grandfather country”, in search of the “Korean Dream” to success; their ethnicity, they hoped, would play as an advantage.

Finding one’s way back to his or her ethnic background is never easy though. Many such members established their stay in Korea as foreign laborers, often staying longer as unregistered workers in the 3D jobs notorious for being difficult, dangerous, and dirty. With time, this attributed to a negative stereotype of the Chosunjok, and they were frequently marginalized for their status. Korea, given its fiercely homogenous society, was not quite the welcoming relative they expected, and the legal process of naturalization was not made easier for the Chosunjok, “dongpo (compatriot)” or not.

Some have made complaints like the following, “The South Korean government grants nationality and financial support to North Korean defectors. Why not to Chosunjok?” and “The Chinese can teach their language and be employed in big companies, but Chosunjoks are deprived of jobs and the right to work during the process of naturalization,” found in the academic paper, Ethnic Koreans from China: Korean Dream, Adaptation, and New Identity by Woo-Gil Choi.

As this shows, being both foreigner and ethnically Korean, the Chosunjok have struggled to come to terms with their place in South Korean society. In many cases, national borders were stricter than biological connection, and this has made much of the Chosunjok community in Korea to gather amongst themselves to strengthen their own sense of ethnicity against the pain of betrayal and longing for true acceptance.

More recently, however, the second generation of these Chosunjok, the children, have come to recognize a new identity of themselves being legal residents of Korea. Although their parents perceive the homeland with a degree of spite, their children do not hold such a negative view. Many of this generation understand their background as Chinese citizens but with ancient connection to Korean history and they accept both cultures as valid (Woo-Gil Choi).

Identity and Acceptance

Identity searching is not easy for anyone. Places, people, and culture shape our identity, making difficult the process of finding a place to be considered “home”. However, there is a common denominator vital for this research: acceptance. “I consider America my home; it is the place that accepts me”, declared Sarah. Perhaps home is where we feel accepted despite all the identity issues. If we were just more prone to accept than to discriminate, the search for identity could rather be a fun ride than a painful rite-of-passage.

Alessandra Bonanomi & Eui-mi Seo, Reporters for The AsiaN