Troubled Waters: Seeking Co-operation Along the Mekong

*Author, Le Dinh Tinh is Deputy Director General of the Institute for Foreign Policy and Strategic Studies, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. The views expressed here are his own.

Once at the center of a long-running war, the Mekong River Basin is now far from the world’s headline-grabbing conflict zones. But the Mekong, one of the world’s longest rivers, passes through countries whose varied national interests have so far prevented the co-operation necessary to resolve many common trans-border problems. Le Dinh Tinh outlines the power politics at play, and why enhanced co-operation is vital to security in the Mekong River Basin.

FROM THE SOUTH CHINA SEA to the Mekong River Basin, water represents one of the most essential strategic attributes of the Asia-Pacific region. In fact, water has become a “new battleground” in Asia, as argued by Brahma Chellaney in his book, Water: Asia’s New Battleground (2011). Containing the 12th longest river in the world, the Mekong River Basin flows from the Tibetan plateau through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam, covering an area of nearly 795,000 square kilometers with an estimated population of 60 million people.1 The Mekong is a vital source of fish, food, and fresh water to tens of millions of people.2

Studies show that, much like climate change, challenges to a vital water system have to do fundamentally with human factors. In today’s resource-strained world, floods and droughts are not simply natural phenomena; they are often caused or worsened by human activities, of which the prime

suspects include upstream dam-building, river diversion and over-fishing, to name just a few.3 These are not isolated causes; they are interwoven into a complex web of relationships between riparian sovereign states in a rapidly changing strategic environment in the Asia-Pacific.

Contending Interests

Against this background, one can argue that the Mekong Basin must be examined from geo-strategic points of view. Unfortunately, the interests of nation-states still prevail. As argued by the late Hans Morgenthau, a theorist of international relations and one of the founding fathers of political realism, “politics among nations” remains essentially a struggle for power and interests.4 In today’s interdependent and interconnected world, that raw assessment of international relations is not sufficient to define how nations should relate to one another; but this is partially what is happening in the Mekong River Basin.

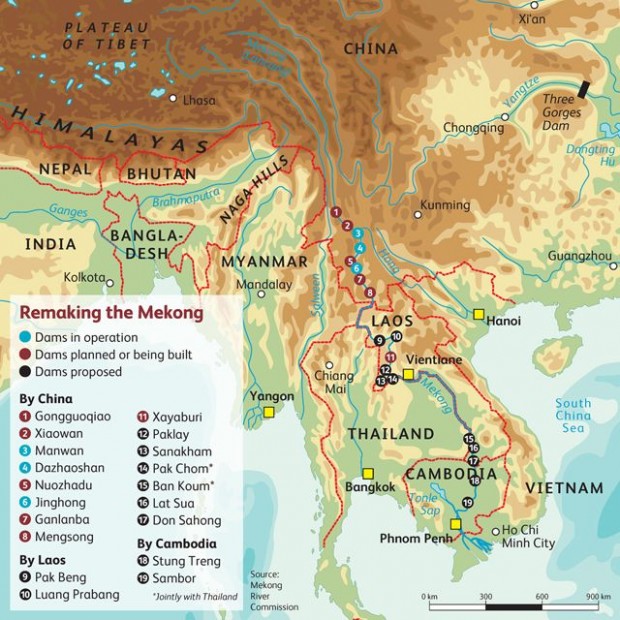

As the biggest riparian state on the Mekong, China places great emphasis on the river — which it names Lancang — as an important source of security and development, particularly for its western and southern provinces. China has three dams already in place on the river upstream and a plan eventually to have up to eight, known as the “Lancang dam cascade.” The amount of water held will total about the same as in China’s Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River, the world’s largest dam.5 In the Lower Mekong, meanwhile, there is only one dam currently under construction, the contentious Xayaburi dam in Laos; work was suspended in December 2011 over concerns expressed by Cambodia and Vietnam, but the developer claimed in August that it was under way again. Meanwhile, several other dams are reported to be in the advanced stages of planning. These projects are a source of controversy among riparian states, particularly between upstream and downstream countries.6

Other major powers have also put the Mekong Basin on their radar screen. The US has recently demonstrated a greater interest in the Mekong area by launching in 2009 the Lower Mekong Initiative (LMI) forum, which is designed to promote collaboration in the areas of environment, health, education and infrastructure development. Strategically, this is one of the latest moves by the US to enhance its engagement in continental Southeast Asia versus its traditional focus on maritime Southeast Asia. This is all taking place in the context of the explicitly stated intention of the US to “pivot,” or “rebalance,” its foreign policy toward Asia. At the Fifth Lower Mekong Initiave Ministerial Meeting in Phnom Penh in July 2012, the US government rebranded it as “LMI 2020” and reaffirmed its pledge of $50 million in grants for projects within the framework of the LMI over the next three years.7

And the US isn’t the only country involved. With a view to increasing its presence and deepening relations with riparian countries, Japan, the biggest donor to the Mekong region, has pledged multi-billion-dollar programs for the Mekong. In addition, South Korea, India, the European Union and Russia — operating via mechanisms provided through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations — have all shown signs they are gearing up their commitments in the Mekong Basin, taking into account the increasing strategic importance of the area.8

So far, though, national interests are proving to be stronger than trans-border interests, according to studies by various donor and research programs, such as the one carried out by the University of Sydney in collaboration with Danish International Development Assistance in 2006.9 When issues are viewed from the perspective of each riparian state along the Mekong, it may seem natural that the protection and promotion of national interests is paramount. But if one takes a regional perspective, demands for closer policy integration quickly become a compelling clarion call. Worsening salinization, increasing floods and droughts, and a lack of access to safe drinking water are concerns shared by all countries along the Mekong and they call out for trans-border solutions, something that outside donors have noted. That is why such ideas as the Policy Dialogue on Watershed Management in the Lower Mekong River Basin, which aims to promote trans-border co-operation, have received such positive feedback.

Institutional Shortcomings

Given the nature of the common issues in the Mekong Basin, it would seem that trans-border co-operation holds out the greatest promise for finding solutions. And yet, efforts to that end are hampered by institutional shortcomings at the regional level. Currently, the most important inter-governmental instrument for regulating river-related activities is the Mekong River Commission (MRC). But it faces a number of challenges in its quest for more equitable and sustainable use and management of this great river. For starters, its members include only Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, not the upstream countries China and Myanmar, although the two have co-operated with the MRC in some areas. As a result, the co-ordination of policies and actions by all stakeholders concerned has remained less than desirable. Analysts in the field often ask: is there really a regional water policy in the Mekong Basin notwithstanding the fact that the MRC is supposed to be a regional water body?10

Part of the MRC’s problems may have to do the perceived political clout of its functionaries. Currently, the MRC Council consists of members with ministerial-level appointments representing Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, but several experts in the field of trans-border co-operation suggest that a higher level of representation is necessary. The inclusion of prime ministers or deputy prime ministers on the MRC Council, for instance, could lead to stronger policy impact and deeper political commitment than the current arrangement.11 In the meantime, questions have been raised as to whether non-state actors such as civil society organizations should take part in this decision-making process.

Another issue is that various national committees and agencies that contribute to the work of the MRC are trapped in heavy bureaucracies that are more national than trans-border in their focus. This is undoubtedly tied to the thorny problem of ceding sovereignty, a common dilemma in any effort to address trans-border issues. Moreover, related mechanisms such as administrative procedures and the exchange of budget information need to be further streamlined to become more efficient and effective. Certainly, this process could be seen from the wider lens of national public administration reforms such as those undertaken by Laos and Vietnam.12

Fragile Relationships

A no less significant challenge is how to manage the relationships both among the riparian states of the Mekong and between those states and the major powers, notably China (also a Mekong riparian state), the US, Japan and India.

In general, it should be noted that the Mekong River Basin enjoys relative peace and stability. But one should not forget the vulnerability of a region where protracted wars and conflicts raged through much of the 20th century and earlier.13 As a report by the Stimson Center argues, given the “hard-won peace and stability” of this region, it is all the more important that issues related to the Mekong should be addressed in a delicate manner.14 The US State Department has highlighted what it views as several factors in the Mekong region that have the potential to lead to conflict: unilateral development of upstream infrastructure, bilateral development of downstream infrastructure, changing environmental conditions and historical tensions in relations between Mekong countries.15

The question of enhancing trans-border co-operation in the Mekong River Basin is definitely linked to larger issues of peace and stability in the region as current sources of inter-state tension are lurking. Though an encouraging degree of progress and goodwill have been reached, Thailand and Cambodia have not been completely saved from conflict over the Preah Vihear temple. In addition, controversial dam projects on the mainstream Mekong are undermining supporters of friendship and co-operation along the Mekong Basin. Elsewhere, Myanmar’s recent moves to reform and move toward democratization have opened up opportunities for the country and the outside world, but they also underscore the fact that the conditions for peace and stability need to be further consolidated in continental Southeast Asia. At sea, tensions are even higher, especially given the current situation in the South China Sea, where China’s nine-dashed line historical claim to the South China Sea is having adverse impacts on not only claimants but also non-claimants in Southeast Asia. The negotiations on a Code of Conduct (COC) for the parties in the South China Sea are not going smoothly, and this could hamper efforts to achieve trans-border co-operation in the Mekong River Basin.

Next Steps

First, the stakeholders should continue to strengthen the MRC by formally drawing China and Myanmar into the fold, elevating its decision-making from the ministerial level to the deputy prime minister level and streamlining its administrative procedures. Central to all of this is that the Mekong states should strictly implement the 1995 Mekong Agreement and related international laws and customs on the equitable use of water resources; all member countries together should make every effort to mitigate the possible negative impact of exploitative activities on the Mekong River.

Second, mechanisms within the ASEAN framework should be enhanced in a way that can strengthen their supplemental support for the MRC. Mekong riparian countries should seriously consider adopting confidence-building and preventive diplomacy measures to improve the climate for trans-border co-operation (transparency, information sharing, dialogue, consultation, prior notification, early warning and good offices).16 Within the ASEAN framework, there is a suggestion that the water resource management question be switched from the ASEAN Social-Cultural Community to the ASEAN Political Security Community, with a view to the securitization of the issues concerned. This is a positive development that reflects the importance of the underlying issues.

Third, on so-called Track II diplomacy, a number of useful activities could be undertaken, such as organizing forums and dispatching fact-finding missions to controversial areas such as borders and dams to raise awareness and generate policy recommendations. For example, the recent series of meetings of the Council for Security Co-operation in the Asia-Pacific (CSCAP) has resulted in a draft memorandum of understanding on enhancing water security in the region, which could be submitted to the ASEAN Regional Forum, the only multilateral security institution that consists of all the important stakeholders in the region.

In short, the water of the Mekong River Basin must be seen as a security issue that calls out for a comprehensive and co-operative solution. If not, the quality of life for the people and species along this great river will continue to erode. For the right things to happen, the nations of the Mekong must be willing to allow for the sufficient erosion of national sovereignty to enable a truly trans-border solution to emerge that will ultimately benefit all. <Global Asia/Le Dinh Tinh>

NOTES

1 Judy Eastham et al., “Mekong River Basin water resources assessment: Impacts of climate change,” Water for a Healthy Country Flagship Report Series (Clayton, South Victoria: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO), 2008), p. 11.

2 Christopher G. Baker, Dams, Power and Security in the Mekong: A Non-traditional security assessment of hydro-development in the Mekong River Basin (Singapore: Center for Non-traditional Security, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 2012), p.2.

3 See, for example, Richard P. Cronin and Timothy Hamlin, Mekong tipping point: Hydropower dams, human security and regional stability (Washington DC: The Henry L. Stimson Center, 2010); Shi Jiangtao, “Contentious dam begins power generation”, South China Morning Post, June 23, 2008.

4 Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Thompson, Politics Among Nations, 6th edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985).

5 Peter H. Gleick, “Three Gorges Dam project, Yangtze River, China”, Water Brief no. 3, in The World’s Water 2008-2009, ed. Peter H. Gleick (Washington DC: Island Press, 2009).

6 The controversial Xayaburi dam case in Laos can support this assumption. See, for example, Paul Wyrwoll, “The Xayaburi Dam: Challenges of transboundary water governance on the Mekong River”, Global Water Forum, Dec. 13, 2011. At: www.globalwater forum.org/2011/12/13/the-xayaburi-dam-challenges-of-regional-water-governance-on-the-mekong/, accessed on July 25, 2012.

7 Hillary Rodham Clinton, Remarks at the Second Friends of the Lower Mekong Ministerial Meeting (Phnom Penh: July 13, 2012). At: www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2012/07/194957.htm, accessed July 25, 2012.

8 See, for example, The World Bank, Regional support for the Greater Sub-Mekong region (October 2007).

9 At: http://sydney.edu.au/mekong/documents/mekwatgov_mainreport.pdf, acccessed on July 24, 2012.

10 See, for example, “Mekong Region Water Resources Decision-making National Policy and Legal Frameworks vis-à-vis World Commission on Dams Strategic Priorities”, Policy Brief, The World Conservation Union (Bangkok, Thailand and Gland, Switzerland: 2006).

11 For example, Dao Trong Tu (Center For Sustainable Water Resources Development and Adaptation to Climate Change) argues that the MRC Council should be upgraded to the level of deputy prime minister. In this case the 1995 Mekong Agreement must be amended, granting the council more decision-making power over important development projects that impact the river system. Read more at: www.stimson.org/summaries/a-vietnamese- perspective-on-proposed-mainstream-mekong-dams/.

12 See, for example, Swiss Co-operation Office in the Mekong Region, “Mekong Insights”, Monthly Newsletter, No. 4, (May 2008).

13 For example, the World Bank 2011 World Development Report (pp. 2-5) warns that violence often works in cycles, and countries that have experienced violence in previous decades are more likely to experience it again due to low institutional capacity. In Christopher G. Baker, Dams, Power and Security in the Mekong: A Non-traditional security assessment of hydro-development in the Mekong River Basin (Singapore: Center for Non-traditional Security, S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, 2012).

14 Richard P. Cronin and Timothy Hamlin, Mekong Turning Point: Shared River for a Shared Future, (Washington D.C: The Stimson Center, 2012).

15 Joseph Yun, Deputy Assistant Secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, US State Department, “Challenges to Water and Security in Southeast Asia”, Testimony to Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs (Washington D.C., Sept. 23, 2010) at www.state.gov/p/eap/rls/rm/2010/09/147674.htm, accessed on Feb. 7, 2012.

16 This viewpoint was circulated by a number of participants during the CSCAP meeting series on water security in Hanoi, Siem Riep, Tokyo and Chiang Rai in late 2011 and early 2012.