Central Asia and Turkey: Playwriting the National Interests

On 17-18 November 2016 Turkish President Recep Erdogan visited Uzbekistan. This visit took place soon after the death of the first President of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, on September 2nd, 2016. For a long time, Uzbek-Turkish relations have been a stumbling block in the advancement of Turkey’s overall policy towards a certain Central Asian region. This region consists of five Turkic nations: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and one Farsi speaking nation – Tajikistan. That is why some observers described this event as a kind of resetting of Uzbekistan-Turkey relations, thereby the opening of a new page in Turkey’s relations with members of Central Asia. This, however, is quite a complicated and multifaceted issue.

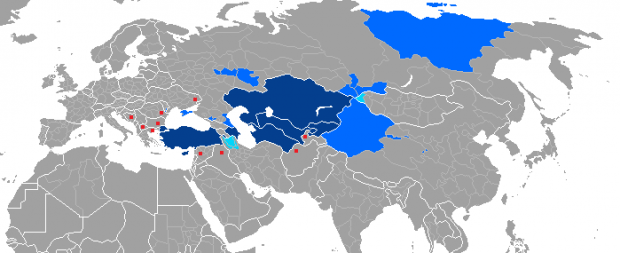

Alongside the Turkic people living in independent states of Central Asia and the Caucasus, large communities of Turkic peoples live in the Russian Federation. And as Turkey considers Central Asia to be part of the Turkic world, Russia considers the same region a part of Eurasia. In the way Turkey implements normative and information aspects of geopolitics to reach out to Central Asia, Russia does the same in its own favor.

By and large, conditionally speaking, Turkey can pursue its policy vis-à-vis Central Asia based on pragmatic, normative and/or an altogether strategic approach. Here, pragmatic policy refers to selective cooperation in spheres which are available for the time being; it is designed for the short-term perspective. The normative policy stems from the principle of ethics and instrumentalizes, among other things, kinsmen and common cultural assets. A strategic approach is designed for the long-term perspective and highlights deeper cooperation and strong support in the international arena (see below). In a way, the normative approach can be a bridge between the pragmatic and strategic vision.

Unity of Turkic nations has constantly been the main agenda of Turkey’s Central Asia policy. Uzbekistan has, until now, stayed under the radar in the Turkic ensemble. This is perhaps indicative of the relatively minor role of the normative kinsmen factor and the major role of the pragmatic national interests in the State’s domestic and foreign policy. Moreover, Uzbekistan adopted a bilateralism principle for the foreign policy doctrine it adopted in 2012 and thereby has refrained from any multilateral formats of international communications, except perhaps with the SCO. Uzbekistan’s return to the Turkic world summits and its return to the leading role in the Central Asian region might be mutually stipulating of political advancements deserving strong support from Turkey. For this to be true, a new rapprochement between Turkey and Uzbekistan is needed.

Before reaching out to the broader Turkic world on the basis of common ethnic, cultural, linguistic, religious and other backgrounds, Central Asian countries, which represent by themselves a smaller Turkic world of its own with the same preconditions, might have already united within their own region. However, they boldly initiated regional integration in 1991 and then so resolutely stopped it by 2006 that one can easily assume that their international behavior is shaped by multiple determinants.

Meanwhile, the prevalence of nationalism in Turkey’s policy regarding Central Asia cannot but contain the elements of delicate pan-Turkism (like pan-Iranism, pan-Slavism, pan-Arabism). Understandably, Turkey cannot dismiss its kinsmen rhetoric and mindset in its dealing with peoples and countries of that region. That is why nationalist and the kinsmen-based policy itself, perhaps, needs some modification and adaptation to contemporary realities. Even if one rationalizes a pan-Turkish stance in one way or another, we should remember that any ethnic pan-ideology came into being in a very specific context of international relations in the XIX-th century that is, during the not-yet-globalized world. Therefore, such ideology has inevitably the legacy and burden of the past. Modern nationalism requires new ideas based on modern democracy and new forms of international life.

When normative and geopolitical reasoning meets the playwriting of national interests, the result is political confusion.

By and large, despite a good start, controversial experience and uncertain perspectives symbolize a retreat from overall intra-Turkic rhetoric and communication. This would be a defeat in Turkey’s strategic position in the international arena. Strategic thinking requires not retreating but retreating (re-reading) Central Asia – on the one hand, and re-reading the “Turkish model” – on the other. The “Turkish model” itself should turn from being a simple static picture into a dynamic process of self-criticism, self-improvement, and self-assertion.

When we contemplate about the adequate Turkey’s strategy towards Central Asia, several relevant criteria for evaluation of the content and efficiency of that strategy could be the degree of mutuality in politics, society, culture, as well as the degree of connection between countries of Central Asia and Turkey. A high degree of connectivity, mutual trust, and friendship of states; their common position on key issues of world politics and international order; comprehensive and long-term cooperation in the sphere of national and international security: all these are reflected in the notion of “strategic partnership”. Can we apply such a notion when we talk about Turkey-Central Asia relationships?

Turkey’s new Central Asia-strategy is expedient, similar to those of the EU, USA, Japan, India and South Korea. This strategy should take into account the previous experiences of a good start and controversial implementation of Turkey’s policy toward Central Asia. Relations should be based on recognition, supporting, and assisting the Central Asian regional integration. Only then would this strategy be an innovative policy that could open a new page in Turkey-Central Asia ties. Otherwise, controversies and uncertainties; mistakes made in the past with Turkey’s Central Asia outreach will only linger.