70 years after it was created … Is DMZ a geographical wound across Korea or a fortress to preserve status-quo?

Despite her young age, Kkonnim Bae understands the depth of the tragedy that has struck her country for seven decades. Amid messages of hope and peace at the DMZ

By Habib Toumi

SEOUL: Seventy years after the bloodshed ended with the division of the Korean Peninsula along the 38th parallel, the past is still very much alive.

The past defines where Koreans live today. South Koreans to the south of the 250-kilometer Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and North Koreans to the north.

My first visit to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the four-kilometer-wide buffer zone set up to stop hostile military actions, was in 2019.

I have heard and read a lot about DMZ as I was growing up, but seeing the DMZ and walking in it enveloped me with an eerie feeling, mixing dramatic history with people’s tragedies without any regard for peace or compassion.

The peculiar silence in the world’s most heavily militarized borders spoke louder than the painful decades of ominous standoff and fatal confrontations.

I felt something similar in Cyprus, but with much less intensity, when I visited the two countries of the divided island in the Mediterranean.

I walked in the capital, Nicosia to the Republic of Cyprus and Lefkoşa to North Cyprus, and heard how the people living in the world’s last divided capital had vastly different narratives, but with the same deep emotions and powerless frustrations.

Yet, people in Cyprus showed off an air of a defiant contentment, an intense joie de vivre that has been forgotten in many united countries.

At the DMZ, an area of 907 squre kilometers, equivalent to 1.5 times the size of Seoul and deeply marked by seven decades of heavily loaded history, such cheerful attitudes were a remote option, an elusive dream.

Ribbions for peace hanging on a fence at the DMZ

Despite its name, the DMZ and the areas around it are heavily armed, heavily guarded and strewn with around 2 million land mines, reinforced by layers of razor-wire fences, booby traps and electronic sensors.

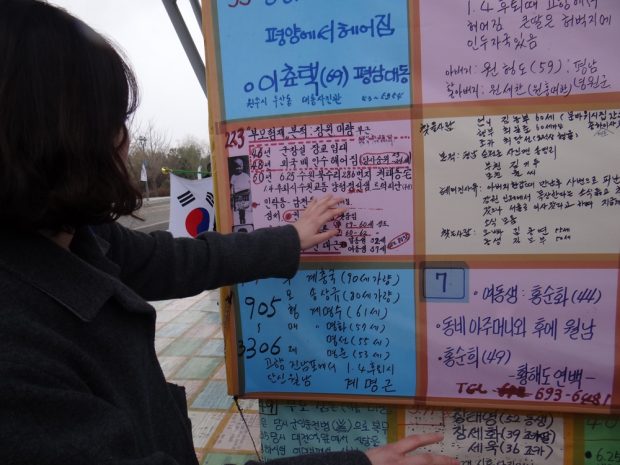

The thousands of colorful messages of hope, dreams and wishes of reunion that included contact details to get in touch with loved relatives are plastered on walls or glued to fences. Colored ribbons with messages calling for peace and reunification are hanging on fences.

They are all very striking reminders of how brutal and distressing separation is and how families, against all odd, cling to the hope that they will see their relatives in the north one day.

They are strong testimonies of how the Koreans whose hearts were torn into pieces felt about their divided countries, separated families, lost ones – A brutal eye-opener on the overwhelming reality between the two Koreas.

I sit at a café overlooking a rusted wagon of a train on the rail line that had linked the two countries, the bunkers, the tunnels dug by North Korea deep under the ground into South Korea and running for long distances past the borders …

The DMZ has been a unique feature in Korea since July 27, 1953 when the armistice was signed following 765 sessions of talks that involved the US, North Korea and China. The situation may last much longer since the road toward peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula remains particularly rocky.

A young Korean woman reads out some of the messages left by North Koreans at the DMZ amid unfading hope they will be contacted by their loved ones

I engage young Koreans sitting at the table next to mine. They are soft-spoken, willing to talk about their hope to put the Korean War to rest in history books instead of a bitter reality marking their daily lives.

However, while the older generation of Koreans seems focused, even obsessed with the Korea reunification issue, the young generation with no memory of living in an undivided Korea or of the tragedies of the war shows less enthusiasm. The present with its opportunities and demands matters much more.

“We understand that our parents and older family members pay so much attention to the issue as it is a strong component of their lives and identity, but to us, it is not so crucial,” one young Korean says.

“Of course, we would like to be a reunited country with greater potential and better possibilities, but we are faring well. We have a strong economy and a happy way of life. We are successful and we look forward to greater achievements with confidence since we know we can do it. We are concerned that focusing on North Korea would slow us down or confine our dreams. We can assist and help them, but we cannot afford to miss good chances if we keep waiting for them.”

Another young girl says that South Korea was a peaceful country that wanted peace to prevail everywhere.

“You can see that even at the DMZ, an area often cited as among the most dangerous in the world, we have a message of peace and we show it ostensibly. There is even a fair that proves that it is so peaceful and safe that people can enjoy themselves while learning about history,” she says.

According to the Korea Institute for National Unification, a think tank funded by the South Korean government, “the public will for inter-Korean integration has been on a constant decline.”

A survey conducted in 2017 found that 57.8 per cent of South Koreans believed that reunification was necessary. The figure is down from 62.1 per cent in 2016 and 69.3 per cent in 2014.

The number of those who said that unification was not necessary if the two Koreas could peacefully coexist without a war was 46 per cent, a 2.9 per cent increase over 2016.

Only 36% of respondents agreed that “our society should pursue unification at the sacrifice of many aspects of our lives”, a decrease by 8.3 per cent from 2016.

According to the study, “the continued crisis phase on the Korean Peninsula since North Korea’s nuclear test in January 2016 seemed to have contributed to a significant increase of a group in favor of the divided state.”

However, the study found that 68.8 per cent of South Koreans believed that the unification would be beneficial to their country, a 12.9 per cent increase from 2016.

Young people say they are not as bitter as their fathers and grandfathers who lived through the war and its tragic aftermath that saw the Peninsula divided into two countries.

However, they believe that their lives would be better fulfilled once their wounded pride as citizens of the Peninsula is assuaged.

Standing with a Korean family as they visit the DMZ. I loved their optimism, especially when they shared the Korean finger heart formed by slightly overlapping the thumb and index finger into a heart shape.

The older generation shares tales of atrocities and talk about divided families, missing people and mutilated memories of dark events throughout more than seven decades.

They point to the pictures and message on the walls and say that the international community owes it to them and to their own conscience to listen to Koreans calling for peace, compassion and prosperity on a reunified Korea.

For outsiders, the world has lapsed into the complacent notion that the division of the Korean Peninsula is a surface wound that bleeds a little, a bit dangerously at times, but it is not an ominous threat to the rest of the world.

They believe the Korean situation is a highly complex issue that cannot be resolved by good feelings and wishful thinking.

They believe that the situation is so crucial for the two countries and people, for the region and for the world that it will never be dismissed and forgotten.