Economics of gold medals

Clockwise from left are SK Group Chairman Chey Tae-won, the family of Samsung Group head Lee Kun-hee, Hyundai Motor Vice Chairman Chung Eui-sun, Hanjin Group Chairman Cho Yang-ho and Hanwha Group Chairman Kim Seung-yeon.

Sports-industry complex powers Korea’s Olympic success

Wherever Korea’s Olympic swimming champion Park Tae-hwan goes, three men follow him like his shadow.

Physical therapist Park Chul-kyu is responsible for helping to relax his body and mind. Personal trainer Kwon Tae-hyun controls Park’s workout routines as well as what he eats. Interpreter Kang Min-gyu smoothens communication between Park and his Australian coach Michael Bohl.

The three men spent with Park 257 days abroad out of the 296-day-long training for the 2012 London Olympics that began last October.

Park’s trio does not belong to the Korean Olympic Committee or the Korea Swimming Federation but to SK Telecom, the country’s largest mobile carrier by revenue.

The team has another member _ Kwon Se-jung who manages the team and joins about a half of the overseas training.

Each team member works for SK Telecom either as a full-time employee or under a contract. It was also the company that combed through the pool of swimming coaches and signed up the Australian coach.

“We are 100 percent in charge of Park’s training,” Ahn Jee-hwan, senior manager at SK Telecom’s sports group, said in an interview.

“It is a demanding form of sponsorship because its structure leaves us fully responsible for the outcome of the training.”

Running the independent training team costs SK 1.5 to 2 billion won a year. In general, athletes secure funding from corporate sponsors and pay trainers out of their own pockets. Ahn said the sponsorship for the swimmer is somewhere between running a professional sports team and funding an athlete.

The sponsorship has gone through multiple tests and evolutions. SK started financing Park’s training in June 2007 and switched the form to running an independent training team for Park for four years until the London Olympics from October 2008. National athletes, in general, train together in the state-run athletes’ villages.

SK outsourced the creation and operation of the team to a sports management agency. But Park’s dismal performance in the 2009 World Championships in Rome raised concerns that corporate sponsorship turned Park into a commercial success but tainted his spirit. The company decided to take over the team completely and run it directly. It restructured the team except Park, the therapist.

“The biggest purpose of the dedicated team was to develop Park into the world’s best swimmer in the 400-meter race in this four-year-long project,” said Ahn.

“It’s a different concept from sponsoring athletes with products or money. It’s a model which athletes would like to benchmark.”

Conglomerates behind gold medals

While Park’s independent training team is a unique form of corporate sponsorship here, how Korean Olympians’ training is supported is unusual in a global context.

Observers may wonder how a small country with a 50 million population, a majority of whom do not practice Olympic sports in real life, manages to win so many gold medals.

Aside from athletes’ natural talents and exceptionally arduous training, heavy support from large conglomerates plays a critical role, experts say.

“In some countries, Olympic sports are practiced daily life. In Korea, it’s different. We call it ‘elite sports.’ We identify and foster talents through intensive training. It costs a lot of money, and without funding from businesses, it will be difficult to maintain the level of training,” Ahn said.

Last year, 10 largest conglomerates spent 427.6 billion won on sports which is half of the budget of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism for sports of 840.3 billion won, according to the Federation of Korean Industries (FKI), a lobby for conglomerates.

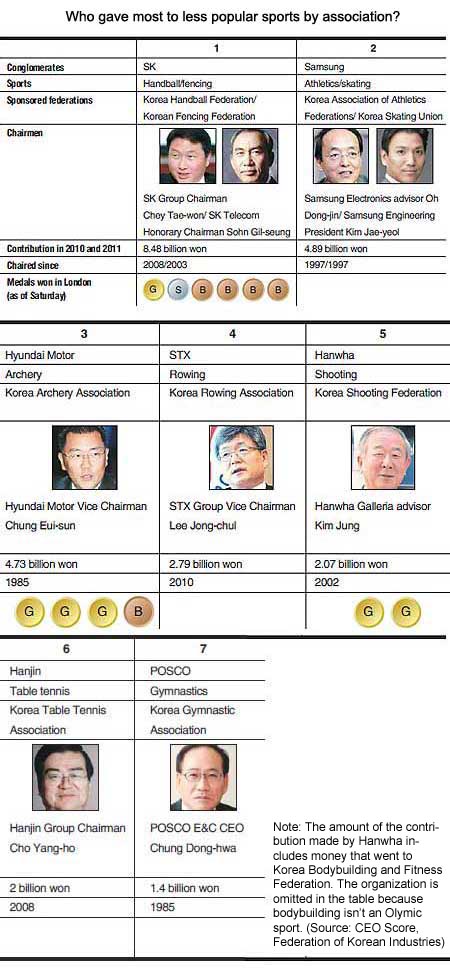

Thirty one percent of the 427.6 billion won went to less popular sports. Financing for amateur sports is done largely in three ways. More than 47 billion won was spent on running amateur sports teams, 14 billion won on associations and governing bodies and 71.4 billion won on campaigning to host and hosting international events, FKI said.

Nearly a half of governing bodies of 58 sports registered with Korean Olympic Committee are chaired by businessmen, with 10 conglomerates heading 10 of them. The 14-billion-won contribution by the juggernauts accounts for some 30 percent of the sports associations’ total revenue at 48.9 billion won, FKI said.

The 10 conglomerates also run 23 teams for 18 kinds of less popular sports ranging from table tennis to archery.

The 132.5 billion won spent last year on amateur sports by the conglomerates nearly equaled the Korean Olympic Committee’s 2011 budget of 133.9 billion won but was lower than the 2012 budget of 175.4 billion won.

The committee received last year 36.3 billion won from the government while 127.6 billion won came from the Korea Sports Promotion Foundation fund, which raises money mainly through running legal sports betting.

The budget covers the whole gamut of sports-related expenses including those for training athletes, supporting their international matches, building new facilities and hosting international events.

In comparison, some other countries have much poorer environment for athletes to secure enough funding for their participation in the Olympic.

The U.S. government, for instance, does not give financial assistance the country’s Olympic committee, which has to raise fund from donations and corporate sponsorships.

Before the summer Olympic, the committee sought a $5 instant donation from visitors to its site, www.teamusa.org, and sold T-shirts.

With the committee’s limited resource, only 30-35 percent of U.S. sports teams’ budgets come from the committee, according to the U.S. business magazine Fortune.

Governing bodies for less popular sports rely on private contribution and membership revenue. In some cases, athletes even take odd jobs or participate in fund-raising events. Fortune said that the women in the U.S. rowing team receives only a $400-a-month stipend from the committee, so takes one or two jobs while training.

“You can say that Koreans athletes train in a happier environment,” said Kim Chong, the professor of Sports Industry and Management at Hanyang University.

Many of sports sponsored by conglomerates have yielded numerous medals.

SK Telecom is one of the biggest winners this year as Park won two silver medals and the fencing team picked two golds, one silver and three bronzes. SK Telecom has been chairing Korea’s fencing association since 2003.

The female handball team has also garnered much attention by advancing to the quarterfinal from the notoriously competitive group with Norway, France and Denmark. SK Group Chairman Chey Tae-won has chaired Korea Handball Federation since its formation in 2008. In 2011, he gave 43.4 billion won to build the country’s first handball stadium.

Hyundai Motor Group is also smiling as the Korean archery team won three gold medals and one bronze.

The country’s largest automotive maker has sponsored the sport since 1985. Chung Mong-koo chaired the archery federation between 1985 and 1997 and has remained an honorary chairman since. The current chief is his son and Hyundai Motor Vice Chairman Chung Eui-sun.

The group said that between 1985 and 2010, it spent a total of 20 billion won on the sport and made special training such as bungee jumping and exploring graveyards possible. At the two Olympics in 2004 and 2008, the company awarded more than a billion won in total to the athletes and coaches.

Why chaebol support amateur sports?

When Jin Jong-oh won Korea’s first medal in the 10-meter air pistol game, Hanwha Group, which chairs the shooting federation, sent out news release on how Chairman Kim Seung-yeon celebrated the victory on his way to Iraq.

“Firstly, funding athletes or sports teams helps a company to enter overseas markets. Secondly, it helps them in launching a new project. Thirdly, it’s for firms’ sustainable growth plan including corporate social responsibility program,” said Kim of Hanyang University.

While sponsoring sports stars may be one of the most conventional marketing methods, the third reason may be the most appropriate for the Olympic Games.

Unlike athletes of professional sports including football and baseball who get constantly exposed in matches held throughout the year, those for less popular sports get a substantial exposure only during the quadrennial Games and minor ones in regional and global competitions held yearly.

At the Olympics, athletes cannot even talk about their sponsors because only official partners for the event can be publicized and advertised.

Ahn of SK Telecom agreed, saying that Korean athletes’ fine performance in the Olympics is believed boost a country’s national glory as well as patriotism and conglomerates want to contribute to it.

Chaebol’s sponsorship for sports started to develop in the 1980s when Korea was preparing for the 1988 Seoul Olympics.

The government encouraged large corporations to support athletes by exempting the cost to fund amateur sports from being taxed as public relations expenses.

“Now, even without the government’s push, businesses are willing to sponsor athletes because they know the benefits,” Kim said.

Another huge reason for funding amateur sports is personal honor associated with it. That CEOs try to chair sports federations is a clear example.

The greatest honor of its kind goes to Lee Kun-hee, who is a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

As the 115-member committee seeks to fill nine vacant seats during the London Olympics, many Korean business leaders, including Korean Air Chairman Cho Yang-ho, Samsung Engineering President Kim Jae-yeol, Daekyo Group founder Kang Young-joong and SK Group Chairman Chey Tae-won have shown interests.

There are four ways to become an IOC member _ campaigning individually without backing from the national government, heading international sports federations, taking important jobs at national Olympic committees and being former medal-winning athletes.

Cho, the chairman of Korea Table Tennis Association, served as the chairman of PyeongChang 2018 Bid Committee while Kim, the husband of Lee Kun-hee’s second daughter, chairs the Korea Skating Union.

Kang has been the chairman of the World Badminton Federation since 2008 while Chey is said to be seeking to become the chief of the International Handball Federation for his quest for an IOC seat.

Any dark side of sponsorship?

While Korean athletes’ performances in international competitions are improving, many of less-popular sports still suffer from the lack of funding.

Much of support for amateur sports traditionally came from municipal governments which have been running semi-professional sports teams by hiring the athletes.

As local governments became heavily in debt, 52 sports team belonging to them broke up between 2008 and September 2011 _ five gone in 2008, six in 2009, 26 in 2010 and 15 by September 2011. Seongnam City and Yongin City lost most at 12 and 11, respectively, during that period, according to an information released to a lawmaker by the Olympic committee.

Local governments still hire a large number of Olympians _ 109 out of 245 in the national team. Jang Mi-ran, the Olympic champion weightlifter, for instance, belongs to the Goyang City government in Gyeonggi Province.

Kim of Hanyang University said that chaebol will increasingly take the role of municipal governments in the future.

For instance, SK Group acquired the women’s handball team of Yongin City when it was on the verge of breaking up.

But conglomerates alone cannot foster such variety of amateur sports. Businesses, at the end of the day, support relatively popular sports that are likely to win medals in international events.

Field hockey is one of the examples that failed to draw corporate funding as well as public interest.

“Even within less popular sports, the gap between the rich and the poor has become more severe,” Kim said. <The Korea Times/Kim Da-ye>