THAAD and anti-Chinese sentiment

Sah Dong-seok – The Korea Times

Anti-American sentiment was once a hot-button issue in Korea. Koreans’ antipathy against the United States flared up amid allegations that their traditional ally has supported military dictatorship for decades.

Arguments that the U.S. turned a blind eye to the military’s massacre of civilians in the southwestern city of Gwangju in 1980 added fuel to the public’s hostility toward the U.S. With democracy taking root in Korea, however, anti-Americanism has waned.

By contrast, little had been said about anti-Chinese sentiment here. However, its roots seem deep.

It’s no secret that the Korean Peninsula had been under the direct influence of the mainland China for a long time, whether it was ruled by the Han Chinese or other ethnic groups. The two Manchu invasions of Korea in the 1600s, coupled with Qing troops’ misdeeds at the close of the Joseon Kingdom, imbued many Koreans with bad feelings about the Middle Kingdom.

Modern history, too, may have affected how Koreans think about China. The Communist Chinese Army’s participation in the 1950-53 Korean War certainly worsened Koreans’ antipathy toward China, but Korea’s spectacular economic growth thereafter has caused many Koreans to be free from anti-Chinese sentiment. Some Koreans even belittled China, which lagged in economic development.

Things are changing, however, with China’s emergence as one of the two superpowers on the planet. Relations _ especially economic _ between Seoul and Beijing have deepened significantly since they normalized diplomatic ties in 1992. Nearly a quarter of the country’s exports go to China, and Chinese tourists account for half of all foreign travelers to Korea.

Now it is said that if China coughs, Korea catches a cold. That might mean that most Koreans have a subconscious fear about their country’s overblown dependence on China, and antagonism toward the world’s second-largest economy has been building up fiercely.

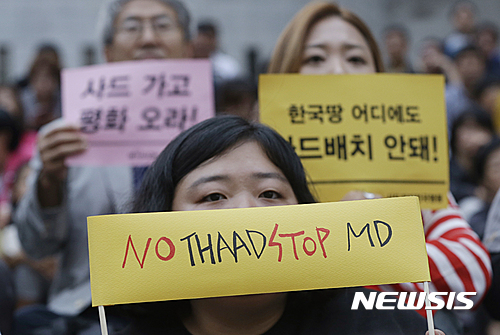

Conflict over the deployment here of a U.S. anti-missile defense system may mark a turning point in relations between the two neighbors that have thrived for decades. True, anti-Chinese sentiment is rising rapidly here as Beijing reacts too nervously and too unreasonably.

Given the sensitivity of hosting the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery, Seoul’s decision may have been too hasty. Beijing’s nervousness about the THAAD deployment is understandable, taking into account that China has strongly protested America’s pivot to Asia.

Even so, most Koreans undoubtedly feel displeased with China’s retaliatory measures, as evidenced by the cancellation of several K-pop events in China and tougher rules on Korean commercial visa seekers. The prevailing view in Korea is that China’s behavior is far-fetched, given that it has only kept a loose rein on North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons but has reacted sensitively to Seoul’s minimal self-defense actions. All of which automatically prompts more Koreans to feel unpleasant about China.

More recently, there have been suspicions concerning China’s overreaction to the THAAD decision. The fact is that China may be attempting to rattle the traditional Seoul-Washington alliance by sticking to the THAAD issue after being checked in its standoff against the U.S. in the South China Sea. This speculation is not necessarily unfounded, considering that China’s state-controlled media have trumpeted in unison harsh accusations against Seoul’s decision last month to host the U.S. missile defense system.

Many Koreans must have felt strong resentment when Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi unilaterally blamed Seoul during talks with his Korean counterpart Yun Byung-se on the sidelines of the ASEAN regional forum in Vientiane, Laos, in late July. His reported high-handedness at the time made them question if their neighborly giant is truly friendly to Korea.

Will Beijing’s Seoul bashing bring fruitful results to China? Not necessarily.

It’s true that Korea could suffer severely if China takes more direct retaliatory measures. But remember that Korea is the largest exporter to China, meaning that the two economies are mutually beneficial. Given that China gains much from its re-export of intermediate goods imported from Seoul under a processing trade plan, Beijing would also inevitably get burned.

What is certain is that Korea’s current conservative administration, led by President Park Geun-hye, won’t be able to reverse its THAAD decision. That’s because no matter how important economic ties with China may be, nothing is more important than national security.

An opinion poll announced by Gallup Korea on Aug. 12 showed 56 percent of respondents favoring the THAAD deployment against 31 percent who opposed it. This represents an increase of 6 percentage points in favorable answers from the survey conducted right after the decision last month by the same polling agency.

Considering that much time remains before late 2017, by which time the Seoul government is to complete installing the missile defense system, China needs to do far more to produce tangible results in the stalled denuclearization talks. To be sure, Seoul has no reason to deploy THAAD if North Korea gives up on its nuclear and missile programs.

Without doubt, China should pay its utmost attention to the spread of anti-Chinese sentiment in Korea it badly needs both politically and economically. China has already felt deep isolation because of its ill-advised territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

On Aug. 24, Seoul and Beijing celebrated the 24th anniversary of their diplomatic relations. What is needed now is for China to be cool-headed to resolve the THAAD conflict with Seoul. Their relations have already matured enough not to be shaken by a single military issue.