Why a cultural boycott of Russia may not be the solution

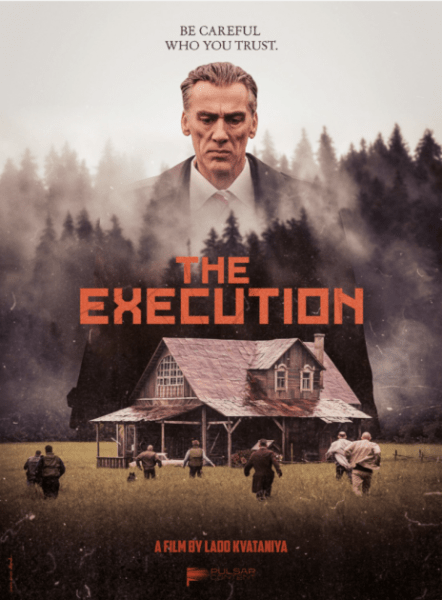

Lado Kvataniya’s The Execution

By Rahul Aijaz

KARACHI: 2022 has brought about an explosion of a conflict that has been boiling for many years – the Russia-Ukraine War, or as it should rather be phrased ‘the Russian invasion of Ukraine’. But it would be unfair for me to delve into the political circumstances that led to this or analyze the potential outcomes or solutions of this conflict as I am not qualified to do so. In this piece, I would rather focus on how we, the world as bystanders and observers, are reacting to it in ways that seems unjust and unnecessary.

Many Russian artists and filmmakers have been openly criticizing the invasion of Ukraine, despite the threat of losing their jobs and being reprimanded. In fact, many Russians have already been arrested for protesting against their government’s actions.

Meanwhile, instances like the Glasgow Film Festival in Scotland dropping two Russian films – Kirill Sokolov’s No Looking Back and Lado Kvataniya’s The Execution – from their edition pose new concerns. The festival released a statement citing the films’ state funding as the reason and “not a reflection on the views or opinions of the makers of these films.”

While we have instances such as the one mentioned above, on the other hand, we have one like Russian gymnast Ivan Kuliak wearing the “Z” symbol (signifying his support of the war) at Apparatus World Cup in Doha, Qatar in early March. A call for disciplinary action has been issued by the International Gymnastics Federation.

Here are two incidents representing the opposite ends of the spectrum, which further complicates the debate. The world’s reluctance to be associated with anything Russian at the moment seems justified, especially if one chooses to look at Kuliak’s actions. But upon more thought, it’s a knee-jerk reaction. Is a cultural boycott of anything Russian an apt response to the war? Is it fair to boycott all Russian cultural and sport ambassadors on the off-chance one or more of them might be in support of the invasion? Is selective boycott possible?

Kirill Sokolov’s No Looking Back

As a Pakistani national, we have seen border conflicts and have been at odds with our larger and more powerful neighbor, India, for the better part of the last 70+ years. The two conflicts may not be compared, but the point I would like to address is, once again, how political and military conflicts serve as a reason for cultural boycotts but the boycotts in fact come across as another form of censorship and mistargeted violence.

One must wonder: does the public have to pay for the crimes of their government? If so, Pakistanis would never be welcome anywhere (although the crimes of Pakistani state and military are mainly against their own people, making the supposed boycott result in cornering the entire population – never for here, nor for there). A better example would be the US, perhaps, with their waging wars across the globe, or Israel with its occupation and oppression of Palestine and Palestinians. But would isolating them be a solution or a dialog with their cultural ambassadors (artists, filmmakers, sportspersons, etc) help us understand each other and voice concerns and engage with each other on a human level eventually bring about social and political change?

Post-9/11, the world trembled at the thought of a Muslim in any gathering, let alone a Pakistani or Afghan Muslim, subjecting them to tremendous amounts of discrimination and even physical harm, not just at the hands of public but institutions and states alike. Having a Pakistani passport was (and still is) a sin that we can’t quite make up for. Similarly, we are now looking to criminalize having a Russian passport.

With Netflix pausing all projects in Russia and Hollywood looking to not release any new films in the country until further notice, the world is essentially isolating Russia in hopes of forcing everyone to pressurize their government to end the invasion. It’s a fine strategy, one may say. But at the same time, it unnecessarily isolates those who are innocent of the crimes and who even fully oppose it. Like Sokolov himself, who has signed petitions against the invasion and whose dark comedy film has nothing politically-driven in it.

If the content of the film does not push any propaganda, then why drop it? As far as state funding is concerned, in an article ‘To Boycott Russians, or Not? In Film and Beyond, That’s the Question’ by Alex Marshall, published in The New York Times, Sokolov shared how around 99% of Russian films made depend on the state funding [including those that criticize life under Putin].

“It’s very difficult to make a movie here without government sponsorship,” said Sokolov.

Therefore, in essence, almost all films – Russian or not – made with the support of Russian state funding are being cancelled. That is isolating an entire region, an entire population who themselves are victims of their state. It’s, once again, reminiscent of the shutting down the voice of South Asian, particularly Pakistani and Afghan, people for a crime they didn’t commit.

In fact, now is the time to give Russians a platform to voice their displeasure and criticism of their government, even if the projects were state sponsored. It’s the right time to help show that being a Russian doesn’t automatically mean pro-war. It’s not the time to boycott all the cultural and sports ambassadors and leaving them voiceless to pay for their state’s crimes in silence.