Strangers in their homeland

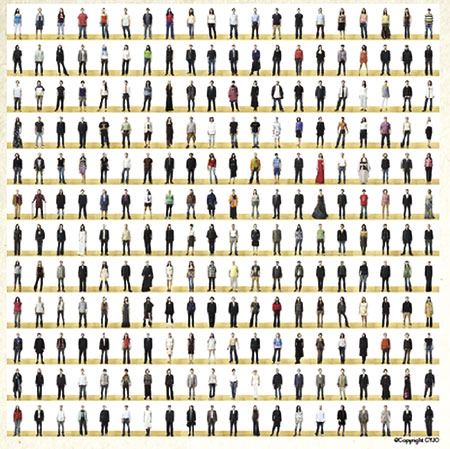

Seen is part of a publication by Cindy Hwang, a U.S.-based Korean-American photographer, in which she took pictures of over 200 “gyopo” or those of Korean descend living abroad in what she called “Kyopo (Gyopo) Project.”

Many ethnic Koreans with foreign citizenship live here and their number is growing steadily. Do these “gyopo,” who were raised abroad feel comfortable in their homeland? Does Korean society embrace them heartily?

A once homogenous country, Korea is gradually opening up to foreigners but it’s still not as friendly to them as it should be as it moves toward becoming a multicultural society.

From language barriers to cultural differences, gyopo experience various hardships because they often find themselves in awkward situations in which they are caught in a conflict between their Korean identity and how people here regard them as foreigners.

It’s hard to live in a country as a foreigner but living in Korea as a gyopo, appearing to be the same as the majority but coming from different cultural backgrounds is complex and confusing. Although many gyopo come to Korea for various reasons ― in search of their national identity or to earn money ― it’s not easy for them to adjust to living in the country.

Benjamin Lee, who was born and lived in Boston, Mass., for 26 years, came to Korea five years ago and is currently working as an English teacher.

“There are many challenging things about living as a gyopo but the worst is that gyopo don’t know what native Koreans are thinking. So, sometimes we come into conflict when we share our opinions or make decisions. Especially, when we share our personal feelings, we think differently because we were raised different way,” he said.

He found differences between gyopo and Koreans when he talked about the future. “Since we have different cultural backgrounds and different lifestyles, in my opinion, Korean Americans have less to worry about than the Koreans. So, when we talk about our jobs and our lives, it becomes a serious conversation because Koreans are very intense about their future.”

Francis Woo, a 27-year-old marketing manager, was born in Korea but raised in Australia and the United States. He came to Korea just to learn more about his roots and now he has landed a job at a startup company.

“Life in Korea is definitely different in many aspects and one major change is that, Seoul is a very fast paced and competitive place,” Woo said. “Things seem more laidback back home regarding life at work and my personal life but in Korea, it seems like survival mode everyday and it’s a very competitive place to be in.”

Since Woo can’t speak Korean, he finds there is definitely a language barrier but the hardest part of living in the country is a lack of support when it comes to settling down and living here.

“The hardest part for me was, dealing with my visa and moving into a new place. There are so many forms necessary to apply for the visa but when I ask for help, it’s impossible to get a straight answer or helpful guidance in order to obtain all the necessary paperwork,” he said.

He said being fluent in English definitely helps him in his workplace, but he said he sometimes feels frustration stemming from the cultural differences. “Sometimes I feel like they look down on me because I didn’t go through hardships in Korea like most do,” Woo said.

Still, he thinks Korea is a receptive place for him so rather than feeling left out, Woo feels he is “finally part of a country” and understands the word “jeong” better now. “Jeong” is the particular feeling of affection for and caring about someone after spending a lot of time together.

Speaking in Korean

A third-generation Korean-Japanese Kim Yoo-hee tries to hide her poor Korean language skills as much as possible.

“I try to be a Japanese tourist rather than speaking my poor Korean when I go out in downtown Seoul to meet friends,” said Kim, a 25-year-old office worker at a Korean branch of a Japanese conglomerate. “That’s because whenever I speak in Korean, I feel people staring at me and hear them whispering that I speak Korean in a weird way.”

Kim has lived in Korea for a year but isn’t amused by the situation even though she knows Koreans are quite closed to Korean-Japanese due to historical reasons.

Whenever conflicts arise between Korea and Japan, she finds her life in Korea becomes more difficult. “Though it happens quite rarely, it’s true that people treat me coldly when I speak in broken Korean. Other than that, I think I have adapted well to life in Korea,” Kim said.

According to the Ministry of Justice, the total number of gyopo living in Korea stood at 510,387 in 2011, which corresponds to 54 percent of the total of 944,170 registered foreigners.

“Gyopo can experience adjustment disorders accompanied by depression, anxiety, and stress because of the cultural heterogeneity, the sense of difference,” said Oh Hyun-sook, a medical social worker of Brian Allgood Army Community Hospital.

“To overcome these problems, they need to realize that anybody can experience these readjustment problems and they are advised to meet people in similar situations to share experiences and enjoy activities such as sports together,” she added.

Fitting well

Of course many gyopo overcome cultural differences and adapt to the surroundings well.

Don Lee, who runs his own information technology company Wable Co, was born on Staten Island in New York and lived in Vancouver, British Columbia, for 12 years. The 23-year-old CEO came to Korea in August last year for the last semester of his undergraduate degree and has been here ever since.

The only difficulty Lee has is the surroundings.

“The intense activity does not stop here in Seoul, especially at my location in Gangnam,” Lee said. “The first one-fourth of my stay in Korea was undisciplined because everything was so new and foreign and exciting. But I quickly became jaded with all the glamour and lights, which has allowed me to live in a healthier and more balanced way.”

Unlike other overseas Korean, Lee has never felt left out or met Koreans who treat people badly.

“I have yet to experience anything negative or been treated unfairly, and that applies to all my other friends that I have been with,” Lee said. “I intend to stay here as long as it takes, until I fulfill my goals with my company.”

Kim, who is working for a media company in Korea, was born and raised in the U.S. He came here in 2008.

“I’m respectful of Korean culture and I understand it, and I think they really appreciate that as well. That has been helpful for me to find the job that I wanted to do in Korea,” he said.

Still, he said that one thing that surprised him is the drinking and nighttime entertainment culture in Korea.

“For me, being Korean-American has been an asset working in Korea. My employer values my Western perspective and at the same time, they feel comfortable because I understand their culture very well.”

He said getting accustomed to the two cultures has more benefits because it made him more well-rounded and competent, so he doesn’t think being Korean-American is a barrier.

Still, he said psychological difficulties about identities could be hard for overseas Koreans.

He added, “There still may be limits to integrating the two different cultures.” He said some Korean people might judge how Korean you are based on how well you speak the language.

“I always don’t feel comfortable with my level of Korean and it is down to me after all. If you are trying to adapt to their system, such as learning the language and culture, they will appreciate it.” <The Korea Times/Baek Byung-yeul, Rachel Lee, Jun Ji-hye>