Kazakhstan’s crisis: Historical comparison to Korean Peninsula’s geostrategic situation in late 19th century

Smoke rises from a government building in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city, (AFP/Yonhap News)

By Jong-eun Lee

Lecturer , International Studies, American University

SEOUL: This week, Kazakhstan has experienced widespread domestic protests, resulting in the intervention of “peacekeeping” troops from the CSTO (Collective Security Treaty Organization) member states, including Russia.

The mass protests began at first, in response to the state’s raising of LPG price, but were also an expression of popular dissatisfaction against the current government’s 3-decades of rule and subsequent political corruption.

The protesters have burned the presidential palace and several governmental buildings, and casualties have increased among protesters and government forces in deadly clashes across the country.

While the crisis continues, there are several early reflections.

1. CSTO is expanding the definition of “collective security”

Similar to other security alliances, such as NATO, CSTO affirms the collective security of its member states. Traditionally, “collective security” is applied to external security threats from foreign invasion.

However, for this crisis, collective security was invoked in response to the Kazakhstan government’s “internal” security threats from domestic protests. (CSTO did try to legitimize the intervention as a response to an “external threat” originating from foreign terrorist actors such as ISIS).

A historical comparison could be made with the 1894 Donghak Peasant Revolution in Korea, when the Joseon Dynasty requested its hegemonic patron, the Chinese Empire, to send forces and help suppress peasants’ uprising led by the Donghak movement.

Kazakhstan President Kassim-Jomart Tokayev (Yonhap News)

- The crisis could become an opportunity for the current Kazakhstan President Tokayev

Previously, Kazakhstan was governed by President Nursultan Nazarbayev for 28 years until Nazarbayev appointed Tokayev as the new president in 2019. However, even after the end of his presidency, Nazbaryeb maintained political control as the chair of the National Security Council, limiting the new president’s authority.

In response to the current crisis, Tokayev has removed Nazarbayev (and his close allies) from the NSC. Since the beginning of the protest, Nazarbayev has disappeared from the public scene. As a further step of distancing from the former president, Kazakh government has also started to call its capital by its former name, “Astana”, rather than by its current name “Nur-Sultan” (The first name of Nazarbayev).

If Tokayev survives politically, he might be able to turn his former patron as a political scapegoat and strengthen his presidential governance, with Russia’s help

A historical comparison could be made with South Korea’s politics in the late 1980s, when then-President Roh Tae Woo permitted investigations (and subsequent political exile) of his predecessor Chun Doo Hwan to mitigate anti-government public opinion, despite being himself a former right-hand man of Chun’s regime.

- Ukraine and US might become unexpected beneficiaries of Kazakhstan’s crisis

Until this week, Ukraine was the main regional theater of military tension, facing elevation of Russian military presence near its border. However, Russia’s intervention in Kazakhstan could compel Russia to pause its military pressure on Ukraine, giving Ukraine at least a temporal security respite.

Though the US has little leverage to intervene in Kazakhstan’s crisis directly, postponement of security tension in Ukraine (which is more strategically important from the US/West perspective) could also be an unexpected relief to the Biden Administration.

The lessening of security tensions in Ukraine, the containment of the security crisis in Kazakhstan (thanks to Russia’s intervention) could lessen the decision burden of the Biden Administration on two foreign policy areas, which could be a welcome relief for the US government overburdened with multiple domestic and international challenges.

The Chinese expression “過火熟食,” which means “a food is being cooked by a passing fire”, might become an appropriate analogy for Ukraine and the US. Of course, if the US and Ukraine do not take advantage of the strategic reprieve they might gain from Kazakhstan’s crisis, their postponed strategic conflicts with Russia could eventually resume.

Russian peacekeepers disembark from a military plane arriving at an airport in Kazakhstan (Yonhap News)

- Kazakhstan’s crisis could become an inflection point for Russia-China relations

Through its CSTO membership, Kazakhstan is nominally an ally of Russia. But Kazakhstan is also a member of the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization and an important hub for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. It also borders China’s Xinjiang province, where the Chinese government faces political tensions with ethnic minorities. Subsequently, China also views Kazakhstan as a geopolitically important neighboring state.

So far, China has affirmed support for the Kazakhstan government’s measures to restore domestic order. If the crisis continues, China might also be motivated to intervene. And even if the crisis is stabilized through the CSTO’s intervention, China might not welcome subsequent expansion of Russia’s geopolitical influence over Kazakhstan. As a result, China might also intervene to balance Kazakhstan’s trilateral relations with Russia and China.

In 1894, during the Donghak Revolution, Japan objected to Joseon’s request for China’s military intervention. To counter China’s influence over Korea, Japan also dispatched its forces to the Korean Peninsula. Soon after, Chinese and Japanese troops deployed to Korea engaged in mutual combat, causing the Sino-Japanese War.

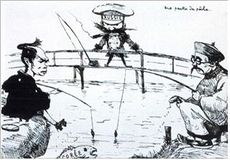

Sino-Japanese War caricature. The title is ‘Fishing Game’. An illustration published in the Japanese magazine Tobae on February 15, 1887 by Georges Vigo of France. It depicts the situation in East Asia just before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War.

Similarly, Kazakhstan’s current crisis could become a testing ground for Russia-China cooperation in Central Asia or become the cause for the next round of “Russia-China split” after the Cold War.

From the US strategic perspective, which is wary of Sino-Russia strategic alignment, if Kazakhstan and Central Asia become a source of geopolitical conflict between the two powers, a Chinese expression 盲龜浮木(“a blind turtle fortuitously find a floating branch”) might be an appropriate analogy. The US could gain a “lucky break” amid difficult international affairs.

Jong-eun Lee