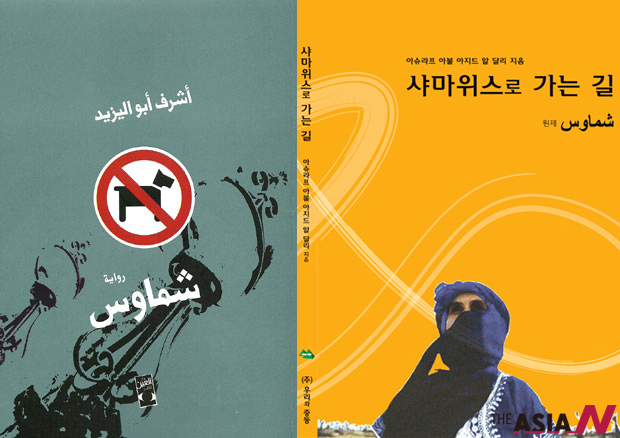

[Novel] The Road to Shamawes ①

*Editor’s note: We start to carry “The road to Shamawes,” a novel written by Egyptian novelist Ashraf Aboul-Yazid, in series. The novel was originally written in Arabic, and translated into Korean and English. The novelist, now working as a journalist in Kuwait, also serves as the editor of the Arabic version of The AsiaN.

Shamawes is not a real place; it is an invented name for a village, that is even new to the Arabic vocabulary!

But this novel, written, published, translated into Korean, before the 25th January revolution in Egypt, had the prophecy to tell what would happen then. The AsiaN shall be happy if you could read and enjoy it.

I may have heard the name “Shamawes” twice or three times before I decided to go there. The distance was less great than the strangeness of the story that led me to it.

The spring temperature heralded a scorching summer. The lines on the laptop screen slowed down and then stopped. That only happened after I had signed on agreement for publishing my first novel!

“You’ll find one thousand and one stories in the alleys of Shamawes”, said a friend of mine.

So, I drove south on the road to Maadi district along the Nile. I passed by a number of neighbourhoods whose high-rise towers are scattered haphazardly on the left, hiding the sun, and preventing passers-by and travellers from seeing the Nile or what is left of it, even through a small hole. These towers were mostly dead, unoccupied, but were only there to deny the neighbourhoods the sun.

After about an hour, and exactly according to the directions, I found the way to Shamawes. I left the asphalted road and drove along a few feddans before reaching Shamawes’s houses. Crossing the wide dusty entrance, which looked like a square without traffic lights, I found out that I had to park the car under the nearest tree because of the narrow inner alleys. A barber was spraying water in front of his shop. His eyes showed he was curious about why I came. I had to reassure him, and perhaps find the first thread of the story with him.

I introduced myself, shook hands and entered the shop. To pay me compliment, he said he read the magazine I contribute to weekly, particularly my articles about politics. That astonished me. The magazine is a monthly one and the last time I wrote about politics I was at university. I gave up politics due to preoccupation with work, or living commitments, but more to trouble and concern.

I asked him to explain the reason behind the name “Shamawes”. As if expecting the question for fifty years he said: “Sir, I’m confused myself. I don’t know whom to believe. Some say it is a Pharaohnic name “Sha.O.Os”; others say the farm was named after the mother of its owner Wassel Pasha. Many others still say that “Shamaseen” (deacons) in St. Maria church lived there before urban development”.

It seems he saw signs of dissatisfaction on my face, so he added:

“You may ask Mr Maaroof Elgindi, who will give you the full answer. As we grew up he was old. May God keep him healthy. Don’t bother with looking for him. The moment you finish drinking your coffee you’ll find him here, he passes by the farm’s houses every day. It is an old habit. May Allah keep your habits and mine!”

In less than half an hour I saw a man whose heavy steps and white beard showed he was over sixty. He used a black ivory walking stick and wore a woollen cap with hand decorations. After introducing me to him, the barber drew a chair from the shop and welcomed the old man loudly:

“Welcome, Mr Gindi. I must thank the gentleman for giving us the opportunity of having you sit with us.”

The barber explained:

“Mr Gindi only greets us when he passes by and only sits in front of his house. May Allah bless him and keep him healthy.”

Elgindi said:

“In 1911, i.e. about a hundred years ago, the area was a grand palace owned by a Turkish man, and about fifteen feddans stretching from here to the Nile, with seven or eight mud slums for a group of farmers. That year, a man named Wassel Pasha came from Upper Egypt. My father, may Allah bless his soul, said the man held the palace’s deed and claimed buying it with its feddans. As the palace became the property of Wassel Pasha, so were the land and the feddans whose workers entered the service of the new owner. A few years later the land was divided among members of Wassel Pasha’s family, the last of whom came here about thirty years ago and built the three villas on the border of the farming land. People of course denounced planting the land with stone, cement and reinforced iron instead of cotton, citrus fruit and palm trees. But what was denounced in the past is the norm today. I can say that the farm’s feddans have been reduced to a half, and I don’t know whether or not our grandchildren will ever see green.”

Taking a sip of coffee, Elgindi continued:

“People here were just farmers. But that was a hundred years ago, because the second generation did not want their children to inherit farming, particularly as he land because of bulldozing became too limited to cater for grandfathers, fathers and children. Well, to cut a long story short, the young began to move to the suburbs on the outskirts of Cairo. Someone bought a car which he used as a taxi between the farm and Maadi. Children received education. The only school in the farm was built as late as the 1950s with the surge of free education in Egypt in general. The farm is now full of mediocre people: Maadi villas’ doorkeepers, porters at Cairo railway station, farmers who do not practise farming. What is new is working in the Gulf. Those who came back from the Gulf; their land, turned it into a poultry farm or rabbit boxes, a thousand and one businesses, except agriculture. Even those who continued farming preferred citrus fruit and potatoes because they are easier to supply to the factories which sell potato chips in bags and fruit deposits in bottles.”

Elgindi looked straight as if he remembered my first question about the name:

“Of course, people here, like those in any community, choose the easier explanation. I’m sure you’ve heard Master Mukhtar’s explanations. But I’ll give you the gist.”

Maaroof Elgindi took the last sip of coffee and passed it on his tongue as if extracting the explanation from it:

“Before Wassel Pasha came from Upper Egypt, the entire land was like a paradise … nothing but shade under its palm and other trees. Sunlight streamed very little. The word “Shamawes” emerged as a diminutive of sunlight (in Arabic) as a grandmother warned her grandson about walking under the hot sun and he replied:

“What sun (shams in Arabic) are you talking about, grandma? By God it’s only Shamawes!”