Toyin Falola Interview Series: Rethinking African Literature in Modern Era

类别: Culture, Society

标签: Toyin Falola Interview Series

By Ashraf Aboul-Yazid

CAIRO: Various African governments have been called upon to create the needed environment for African literature to thrive so as to ensure that the fight against terrorism and the fostering of unity on the African continent can be achieved, just as this would aid the better representation of Africa’s interests in the global space.

This charge was given by the Pan-African Writers Association (PAWA) which was part of a team of panelists at the last edition of the Toyin Falola Interview Series held on Sunday, August 7, 2022, and aired on various social media platforms. The panel was chaired by Professor Toyin Falola. An African intellectual legend on both the continent and in the world, Falola is the Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities and University Distinguished Teaching Professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

Toyin Falola (1953) is a Nigerian historian and professor of African Studies. He is currently the Jacob and Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities at the University of Texas at Austin, USA. He joined the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin in 1991, and has also held short-term teaching appointments any other academic institutions in the States, Europe, Australia, and Nigeria On 31 December 2020 he earned an academic D. Litt in Humanities from the University of Ibadan, in his home city.

Falola has also received honorary doctorates, lifetime career awards and honors in various parts of the world, including, The Lincoln Award, Nigerian Diaspora Academic Prize, Cheikh Anta Diop Award, Amistad Award, SIRAS Award for Outstanding Contribution to African Studies, Africana Studies Distinguished Global Scholar Lifetime Achievement Award, Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Letters, Fellow of the Historical Society of Nigeria, and The Distinguished Africanist Award. He has also received honorary degree of doctors of letters from thirteen universities. He authored and co-authored dozens of books on Africa.

Talking of trends in African Literature Toyin Falola arranged a discussion panel with prominent members of the Pan-African Writers Association under the leadership of the prominent and visible writer, Dr. Wale Okediran, for his famous video series “Toyin Falola Interviews”. He wrote: “To set the historical background to the conversation; the relationship between literature as a human endeavor and society is symbiotic, where the influence flows both ways, and one is shaped by the other.

It is an interesting relationship to study, especially when one considers how literature changes form and intent over time, depending on society’s state of decay or otherwise, and also how society changes over time, sometimes due to the fierceness and unrelenting clamoring of literary figures and the body of work they have produced. It is not certain which has more influence on the other; however, it is established that literature, being the mirror of life and human societies, draws the inspiration for its content from societal happenings.

Notwithstanding, literature acts as society’s conscience, bringing to light the ills in the darkest parts of society, critiquing, acting as a medium for the call to change, and bringing about the needed revolution.”

Toyin Falola explained: “In African literature, society has a rich timeline and has enjoyed many defining moments that we cannot possibly fully expound. For Africans, literature has been a significant part of our societies for longer than the western world represented in their earliest literature of Africa. Long before the colonial and the pseudo-civilization eras, Africa had its proper literature, although this form of literature was not always documented in the written form.

In some communities, pre-colonial African literature was preserved by griots, praise-singers, poets, drummers, and priests, who were the custodians of our collective literature. This was passed down through their family, from father to child.”

With a historian mind, he confirmed: “Literature was a means for several endeavors then. It served as a way of orally preserving the histories of clans, villages, cities and their peoples and guarding the societal norms and beliefs that were the fibers holding the cultures of several African societies together. Beyond this, literature was also a means of interpreting the mystic and divine and showing reverence to the divine. The creation story and the existence of the divine are native to several African cultures and languages.

Furthermore, literature served as a medium for acculturation and enculturation, helping the new members of society to understand the modus operandi and what they needed to know to develop into acceptable members of society. In Africa oral literature was didactic. No matter how entertaining the story or how intriguing the ballad is, regular pieces contain some lessons between their lines and statements.

Many of the written literature by African writers during the colonial and early post-colonial era was targeted at correcting the erroneous narratives that non-African writers and explorers had written about Africans.”

I had the honor to join this rich conversation. Being asked of the debate that is still raging about the chosen language of African literature, and what languages are preferred for writing and publishing modern literature; I said that -in your opinion- that a thousand years ago we could talk about the supremacy of Arabic, or Hausa and Swahili languages in Africa, and at the present time the linguistic supremacy may be a choice between English, French or Spanish, on a global scale, and it may turn after thirty years to other dominant languages such as Chinese and Russian.

In said that “the aim of choosing the language justifies the means to do so; if literature is directed locally for education, enlightenment, communication, entertainment and creative expression, then there is nothing better than the native languages to do all of this. But if we want to choose from this available literature in local languages what represents us before the world, let our evaluation be a choice of the best pieces of literature to be transferred into a foreign language.”

Professor Toyin Falola asked: How successful was the experience of translating Arabic literature in Africa into European languages? My answer was: “Naguib Mahfouz’s winning of the Nobel Prize in 1988 was a turning point for Arabic literature, in general, and the Arabic novel in particular. If we differentiate between the Arab in East and West in dealing with and translating the literary product, the Francophone contributed to the translation of Arabic literature in western North Africa into French and Anglophone did so into English; as if translation into the European languages was attached to the colonial legacy and its language.”

I added: “in the 21st century, the graphic map of translated Arab literature witnessed an advancement movement, due to the political scene of September 11, and then the Arab Spring, In addition to the tangible support from the Arab Gulf states, which came in the form of prizes for novelists, especially in Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, and finally Libya. However, this transfer from one language to another remains limited, and its impact did not go beyond the alley of research and critical literature to the field of public intake of it.

You cannot discuss a general reader in Europe in the Arab-African literary production, except within the limits of the writer who won a Nobel Prize, and another who was associated with, but not considered an elite despite numerous translations because of his opposition to the regime.

I was keen to promote the art of literary anthology production is currently emerging as an important haven to selects texts that are the best according to the editors of the anthology, and evaluate this experience in Africa. At the Ibadan Literary Conference held last June, I acquired several anthologies, either by purchase or as gifts. The most important of them was (Voices That Sing Behind the Veil) for short stories from Africa and its diaspora.

I take it as a starting point to talk about the importance of this art; Anthology, in presenting a panoramic and capsule scene that fits the breathless age, and covers the tastes of readers so that the book turns from the drawer of literature into the hands of common readers.

I read many stories, one for a writer who takes advantage of his medical background to present us with a world and a society rich in details, and does not miss rituals and traditions; another writer, who will move our continent from a mental image of retardation to a post-utopian and dystopian world that he calls in his scientific imagination of Melantopia.

A short story teller takes to talk about swindlers, who might live a few meters away. It is an anthology that really deserves to be a model for generations and geographies as well. There is a model in Kenya presented by the poet, writer and playwright Christopher Okemwa, who attracts African and world poets in anthologies under the themes of justice and hope after Corona. His anthology exceeds a thousand pages, and with African participation in English.

I also showcased my project: The Silk Road Creations Series which began with a number of anthologies: Asia Sings, Mediterranean Waves, Ancient Egyptians – Contemporary Poets, One Thousand and One Nights – One Thousand and One Poems. I am proudly announced that the next edition will be (For Africa). We need anthologies to bring more readers to the literary world of Africa, to go out of its closed circles to the public ones.

Finally Professor Toyin Falola asked me: “How could online events help spreading African Literature for communities of common readers, especially for the new generation? My answer mentioned that everyone has his or her own tool for accessing the Internet, and the literary community has begun to pay attention to the importance of communication and presence through the many applications available in this space. In light of the Covid-19 crisis that swept the world during the past three years, many activities moved from the ground to that alternative space.

That is why I see the importance of producing literary programs, festivals, and interviews, as well as creating a kind of African archive of the literary product in all its languages. Building a stock of live events and encouraging the addition of a documentary repository available to African users and researchers around the world will be useful for current and future generations in addressing and dialogue with this heritage, and interacting in favor of the dynamism of African literature.

As Professor Toyin Falola said: “African writers of this era were tasked with finding their voice, discovering their identity, and what the identity of African literature should be, revisiting falsely told stories of Africa, and orchestrating a literary rebellion to support the fight against colonialism and for independence across African regions. Ahmadou Kourouma and some other francophone authors led the charge for the Africanization of French through written literature during this period.

Chinua Achebe of Nigeria also had his novel, Things Fall Apart, to depict civilized African societies before colonization and the real effects of and reason for colonization. This was also a period when African authors joined forces with political movements and other organizations and associations across the continent to push for the independence of African states.

He wrote in his introduction to the interview: “The role of African literature in the struggle for independence cannot be sidelined, as movements like the Negritude of Sedar Senghor, Leon Damas, and Aime Cesaire contributed to the earliest early political consciousness among Africans, and Sedar Senghor went on to become the first elected president of independent Senegal. Independence came for Africa, heralding a turn in the trend for African literature.

This was not so much different from what writers were tasked with during the colonial era. The earliest period of the post-colonial era jolted African writers to the reality that freedom from colonialism and European rule was not necessarily freedom. Several African leaders who had championed their countries’ independence and were also writers who contributed literature to speak out against colonialists’ oppression soon became what they fought against. The leaders who took over the reins became subjected to neo-colonialism, selfishness, and greed, all at the expense of their country’s development.

Thus, writers became tasked with representing this oppressive and regressive turn of events for several African countries — albeit now independent — through literature. Some of the writers tasked with this work, using prose, poetry and drama, include Wole Soyinka, Ken Saro Wiwa, Remi Raji, Niyi Osundare, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o, Femi Osofisan, Nadine Gordimer, and Abdulrazak Gurnah. It did not help matters that civil wars and intermittent military takeovers rocked some of these newly independent African countries.

There were cases of gross violation of human rights, corruption, and a heart-rending lack of direction. Many of these writers braced incarceration, and some had to relocate to other countries. They were fierce and held the fort to make literature one of the few things the world respected Africa for during the early to mid-post-colonial era.”

To conclude Professor Toyin Falola’s points of view, he said:”Africa’s case is so peculiar that the problems of decades ago, which served as the subject of many a literary work, largely remain the problems of the contemporary African continent.

Among other things, contemporary African writers are tasked with writing about the issues their literary ancestors and mentors addressed. Much of contemporary African literature still centers on political ills, the underdevelopment of several African countries, and neo-colonialism, and it circles back to the identity of the African person in a dynamic and fiercely conscious world that is more conscious and sensitive than it has ever been.

Contemporary African writers, from Kwame Dawes to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Assia Djebar, and Sello Duiker, among others, write about identity, feminism, and the backward cultural and religious practices that marginalize some African women, especially in Northern Africa. One trend that has stood the test of time among African writers is that they do not stop at writing.

They grant interviews, speak at events, and hold discourses all channeled at bringing about some development and improvement to the African continent and the lives of the African people. It was the same with the earliest African writers of the colonial and early post-colonial era, which is how it is with contemporary writers. Technology and the digitization of literature is another trend worth noting in the African literature space. This has increased the number of self-published authors, making writing a profession easier to venture into.

In a period where writers do not need to depend on publishing houses and elaborate marketing and book promotion strategies, the freedom to express and influence is becoming more accessible. There is also the embalming of literature in the digital footprints of the metaverse using non-fungible tokens (NFTs). The questions for ardent followers, critics, lovers, stakeholders, and enthusiasts of African literature are: What is next for literature in Africa? What needs to be done? How are writers being made? What should be rethought?

On Sunday, August 7, 2022, the Pan-African Writers Association, in collaboration with the Toyin Falola Interviews, held a discourse on “Rethinking African Literature.” The goal was to extrapolate issues and arrive at progressive solutions.

A medical doctor, former ANA President and award winning, prolific author whose book is on the reading lists of several African countries, Dr. Wale Okediran is the Secretary General, PAWA (Pan African Writers Association), the continent’s apex writers’ guild. Also the founder of Ebedi Writers Residency, Oyo State, Okediran was a former member of the Federal House of Reps. he responded to questions on the workings of PAWA, how he has been advancing the cause of literature on the continent and the high stakes for African writers.

Dr. Wale Okediran, General Secretary of THE PAN AFRICAN WRITERS ASSOCIATION (PAWA) gave detailed answers of the association present and future, explaining how PAWA assisted in the promotion of African literature since its establishment about 30 years ago. PAWA was founded in November 1989, as a cultural institution born in the larger crucible of Pan Africanism, that is, an umbrella body of writers’ associations on the African continent and the Diaspora.

The mission of PAWA, unanimously accepted at its inaugural congress in November 1989, in Accra, Ghana, is “to strengthen the cultural and economic bonds between the people on the African continent against the background of the continent’s acknowledged diverse but rich cultural, political and economic heritage.” PAWA helped in translating books written by African writers in its authorized languages; English, French, Swahili and Portuguese, in addition to organizing literary conferences, seminars and competitions. The most recent competition was devoted to poetry in those mentioned above languages.

Dr. Wale Okediran took the chance to explain how poor funding is affecting PAWA’s activities and limited them: “Funding remains PAWA’S main challenge. Though the African Union mandated every African country to pay an annual subscription to PAWA, very few countries have been doing this. Even when this is done, the subscriptions are rarely regularly paid. The result is that PAWA is currently unable to execute many of its activities. In addition to poor funding, the inactivity of some national writers associations has affected the activities of PAWA in the affected countries.

This is because, even where active writers exist, as long as these writers are not under any active national writers association, PAWA cannot work in those countries. Although PAWA’S Constitution empowers the association to encourage every African country to have an active national writers associations, it is often difficult for PAWA to do this in order not to be seen to be interfering in the affairs of sovereign African countries.

It is my hope that the new PAWA Council, which has representations from the five geopolitical regions of the continent, will find a lasting solution to this. We had a congregation of writers from about 40 countries at the University of Ibadan. We believe that this congregation of writers is strong enough to move ahead with the agenda of using literature to promote African unity and fight against terrorism and insurgency on the continent.” Dr. Wale established the Ebedi International Writers Residency in Nigeria which has been identified as a big boost for young and emerging writers to horn their skills.

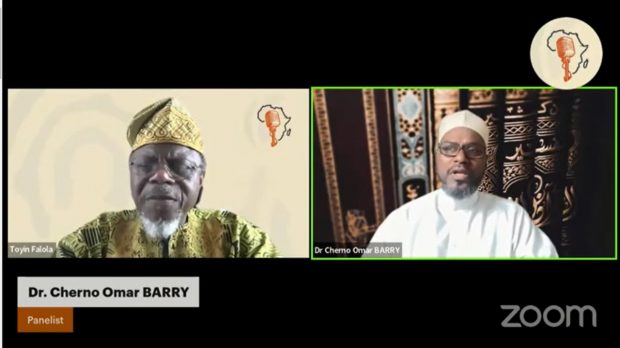

Dr. Cherno Omar Barry was also one of the panelists in this 3 hours long interview. Dr. Cherno Omar Barry is the current Vice-Chancellor of the International Open University, President of the Writers Association of The Gambia (WAG), Former Executive Secretary at the National Human Rights Commission and Permanent Secretary in several ministries, including the Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Ministry of Youth and Sports, Ministry of Higher Education, Research, Science and Technology and Office of The President of The Gambia.

He shared his perspective on disruptive narratives in African literature today, explaining how can we define modern African literature from a gender perspective. He gave a guideline for African writers to respond to the ever-increasing issues regarding Africa with Poor governance, term limits, military take overs, migration, high debts, and corruption that obstacle the scene trying to redefine our African Literature going forward, amidst all these crises. When I took the chance to give my answers in Arabic and English, Dr. Cherno Omar Barry gave his explanations in English and French.

The following panelist was Mwamwingila Goima Peter, an author/writer of children’s and adult literature using Kiswahili. He loves different arts, especially drama and music. Mwamwingila was born in Tanzania in 1981, the fourth of five children in a family of an economist father and an accountant mother.

Although his father played a great lot in molding him to become who he is today (literature man) by giving him bedtime stories during his childhood, he and his father did not enjoy that for quite long enough since his father wanted him to take mathematics in studies and to be like him. He could do something that led them to separate because he preferred art subjects, English and History.

They were enemies until when it was declared that he could never turn out to be an economist or a mathematician but an artist. Finally, his father admitted him again as he was his favorite child. In 2009, he started putting his literature into writing. After ten years, he published his first children’s book Chifu Mtalimbo following a special request by his son Mtalimbo, who asked him for a gift on his birthday. The boy specifically mentioned to him that he wanted Waswahili tales and not otherwise.

Because of his love for children, he made one for him and, since that year, has been publishing one after another. His published literature works are Chifu Mtalimbo, Kisa cha Punda na Pundamilia, Kisa cha Simba Mtu and Babu yangu anajua kila kitu -1. All these he wrote to promote tourism in the country.

He has also been facilitating other writers, encouraging them to pursue their ambitions, mentoring various independent writers and those under the Mtalimbo Books Project, and serving a contract with Tanzania Fasihi Fund – TAFF, a community-based organization to mentor children who learn to write stories. Under the children’s writer program, he managed to recruit six new talents and help them by molding their ideas into stories and later publishing their collection of stories in two different books.

In 2021, he was detained in the most dangerous prison in Tanzania as a civil prisoner. This act was a major setback to businesses and his career since he lost communication with different people and organizations. Still, to him, it was a rare opportunity to learn about life in prisons. While in prison, he managed to start a class and spend his most precious time teaching local people and foreigners how to read and write.

He also taught people how to write storybooks and entertained other prisoners with novels that his friend Husein Wamayma brought him. The writers under his incubation had lost hope of achieving their writing goals, and some even abandoned writing. Still, when he got out, he managed to assist in finishing his previous project. One of his students published a book titled for TUMAINI (HOPE) about inclusive education for children with special needs.

At the moment, he is on the special committee of which he is one of the appointees to mobilize more writers to join together for the national writers’ association. He has been one of the writers who keep on encouraging more people to write to further African literature. His contribution in the interview was to answer these questions, in English and Swahili: How will African writers engage African children to take part in positioning African literature in the modern world considering that the world is a village?

When we say “RE-THINKING…” it is obvious there is something somewhere which is not okay or rather outdated in today’s world; can you tell us what you think about why re-thinking and why now? Since there is so much interaction between Africans with the rest of the world; how can African writers give assurance to the survival and advocate of African children in literature? A question of Mother Languages in Africa is still uncertain in advancing African literature to the rest of the world; what are your suggestions on the best ways to overcome the language barrier of Kiswahili as the new UN language.

The fifth panelist was Monica Cheru , the Vice-President of Pan African Writers Association (PAWA) , South region, and the current chair of the Zimbabwe Writers Association. She sits on the board of the Zimbabwe International Book Fair Association. She is the author of short story anthologies Chivi Sunsets and The Happy Clapper. Cheru’s short stories also appear in multi-author compilations, including Nothing to See, published by Uganda’s Femwrite.

Cheru is an academic author with textbooks in use in primary schools. She has written papers for journals such as BUWA! and presented papers at different fora such as the China Africa Institute for Cultural Studies. A trained storyteller with The Moth, Cheru is a multi-platform digital storyteller, senior media practitioner, and digital footprints strategist.

Monica Cheru raised a lot of issues, regarding the African books availability, the African literature languages, and the sake of writing itself. One of the amazing points she announced ia how to reconsider the colonial languages as part of the African history and its literatures.

TF Interviews: A Panel Discussion on African Literature recorded for YouTube: https://youtube.com/watch?v=GN6IcDGTAzE